Roughly 680 of America’s remaining World War II veterans die every day. Learn about some of the last of the Greatest Generation.

The refrain of an old Army ballad, made famous by World War II Gen. Douglas MacArthur, goes, “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.”

The truth is, America’s remaining World War II veterans—most at least in their late 80s—are leaving us; about 680 die every day, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs. In a few years, the last page will turn on these living, breathing history books, men who fought a war that resulted in more American battle deaths and wounded than any other U.S. conflict. Despite a wealth of documentary films and oral histories in the archives, countless stories of average citizen-soldiers remain untold or forgotten.

“It is sad to see that these simple heroes are leaving us at such a fast rate,” said Floyd Cox, volunteer administrator of an oral history program at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg. The museum has collected 4,400 histories, but most are locked in vast archives and none is available online. Volunteers remain busy capturing stories from veterans before the program inevitably winds down.

In honor of Veterans Day (November 11, the anniversary of the armistice that ended World War I in 1918), I interviewed more than a dozen Texas World War II veterans. They were mostly small-town and farm-raised kids propelled into deadly situations, living to tell how they survived parachuting into enemy territory, fighting in hand-to-hand combat, firing mortars and suffering frostbite, being stranded in the vast Pacific after the sinking of their ship and escaping a burning tank. Some opened up after years of reticence; some shed tears. One vet and his prewar bride demonstrated their everlasting love, and many told of their unfathomable will to live and immense gratitude.

Now, some 70 years after U.S. troops were pulled into the war, we get the rich details of lives so cruelly interrupted.

‘We didn’t even know where Pearl Harbor was’

On December 7, 1941, 17-year-old Jetty Cook and some buddies heard the news after they watched a matinee of “Sergeant York,” the World War I movie starring Gary Cooper.

“Extra, extra! Pearl Harbor attacked!” a paperboy cried.

“We didn’t even know where Pearl Harbor was,” Cook said of Japan’s bombing of the Hawaiian military base that instantly drove America into war.

A year later, Cook left his hometown of Big Spring and enlisted in the Army Air Corps. In the following months he trained as a gunner on a B-17 bomber.

On July 20, 1944, on a bombing run over Germany, his aircraft was hit by flak, which caused two engines to fail and another soon to catch fire. The plane limped westward as it slowly fell from the sky. The airmen jumped just before the bomber crashed somewhere in German-occupied Belgium. Cook parachuted, landed safely, quickly gathered up his chute and hid in some bushes. He watched as German soldiers captured fellow U.S. troops, narrowly escaping detection by a Nazi soldier and his dog.

When the coast was clear, Cook walked westward, drank from a muddy puddle and after midnight took a chance by knocking on the door of a modest farm house, not knowing whether he was in Germany. A farmer gave him some bitter coffee, black bread and shelter in a hayloft. The next day, a member of the Belgian Resistance questioned him at length to ensure he wasn’t a German plant.

Over the next two months, a cast of Belgian partisans took turns hiding Cook, who often posed as if he couldn’t hear or speak. He was periodically reunited with some of his crewmates and shuttled to safe houses, including a room over a bar frequented by German soldiers, a brothel (also visited nightly by the Germans) and a convent. He participated in a bank robbery to obtain food rations, helped a team of Resistance members blow up a railroad bridge to send a trainload of German troops to their deaths and helped capture German Gestapo agents after American and British forces began to liberate Belgium.

Cook and a fellow airman narrowly escaped death when a group of Belgians, emboldened by the retreat of German forces, captured them and put nooses around their necks, insisting they were German spies as they dragged them to a lamppost to be hanged. Then a young Belgian woman stepped up and said she knew the local police chief secretly housed an American and insisted they check. They phoned from a nearby store and verified Cook had been hiding out with the chief’s family. Within minutes, they broke out bottles of wine and they all celebrated.

Cook eventually made a career in the Air Force. Over the years, he returned to Belgium numerous times to reunite with people who aided him and attend anniversary events. Today, Cook, 88, lives in Hunt with his wife of 42 years, Wanda.

‘They were bayoneting and shooting everything that moved’

On May 18, 1942, five months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, Arwin J. “Jay” Bowden enlisted in the Marines. One of eight children born to a cotton farmer and his wife near Vernon in North Texas, he had just graduated from high school.

By November 1942, Bowden, quickly trained as a radio operator, was shipped off with his division to New Zealand, where they set up a defense force to guard against a possible attack by Japan and built camps for troops. Within a year, Bowden and his regiment entered their first combat at the Battle of Tarawa, a strategic atoll about 2,400 miles southwest of Pearl Harbor that U.S. forces needed to refuel aircraft and serve as a launchpad to retake the Philippines and, eventually, attack Japan.

Japan had built a landing strip on Tarawa’s main island and fortified the island with many stockades, firing pits, underground tunnels and concrete bunkers protecting big guns aiming down the island’s lagoon and beaches. One Japanese commander said it would take “1 million men 100 years” to conquer Tarawa. “This was probably the most fortified 290 acres in the world,” Bowden said.

Before dawn on November 20, 1943, Bowden was aboard a troop transport with about 2,000 Marines, part of the largest U.S. operation in the Pacific at the time. He was among troops sent ashore on landing craft known as Higgins boats, but his boat got stuck on a reef. He and 32 other Marines boarded two amphibious track vehicles to get ashore. As they approached the beach, the Japanese blew up Bowden’s vehicle and killed most of the men who were with him.

The fire burned off nearly all of Bowden’s clothes except his boots, knife belt and the leggings he wore under his uniform. His right ear was nearly burned off, as was most of his hair. He dove into knee-deep water and then hid with five other Marines behind a second vehicle. They nursed their wounds and stayed there as Japanese soldiers aimed their weapons at other targets. Near dusk, they decided their best hope was going into deeper water—to the reef about 500 yards out, where they hoped for a rescue.

Earlier in the day, Bowden had picked up a waterlogged rifle that was useless except for the bayonet at the end. As they moved out, Japanese soldiers spotted them by the light of the fires on the island. “They came out and they were bayoneting and shooting everything that moved,” Bowden said. Several enemy soldiers came near, and Bowden somehow got close enough to one of the Japanese carrying a machine gun to plunge his bayonet into his chest.

In such an adrenaline-charged moment, “you don’t know where all your energy is coming from, and you don’t remember where or when. Anyway, I survived,” Bowden said.

He and the two other surviving Marines scrambled away and were picked up by a U.S. ship on which they received immediate medical attention before being sent to a hospital in Honolulu.

Meanwhile, after 76 hours of fierce fighting, the Marines took the island but suffered more than 1,000 deaths and 2,000 casualties, while the Japanese lost more than 4,600 troops. Tarawa shocked the nation for its high cost in U.S. lives and was the subject of a documentary that won an Academy Award in 1944.

Bowden, 89, recovered after six weeks of medical care and returned to participate in other battles in the Pacific. After the war, he spent most of his work life at Southwestern Bell. He is a widower and lives in San Antonio.

‘I was thrilled to death because he came back whole’

It was 1939 in a small town in Oklahoma when Marion Henegar, 21, married his sweetheart, Oletha, just 17. By 1943, Henegar had entered the Army Air Corps and spent three years as a radio operator on a C-47 that hauled supplies and paratroopers to the front lines in Europe.

To drop parachutists, Henegar’s aircraft often flew low, just 650 feet above ground, plenty close enough to be shot down by the Germans. “When we got back, we’d count the holes in the planes,” Henegar said.

For three years, Henegar and Oletha corresponded constantly. “We wrote sometimes once a day, sometimes two,” Oletha said.

Oletha sent her husband care packages with ground coffee, canned milk, pecan pies and—once—a pair of boots better-made than his Army-issued pair. Because of weight limits on packages, she sent each boot separately.

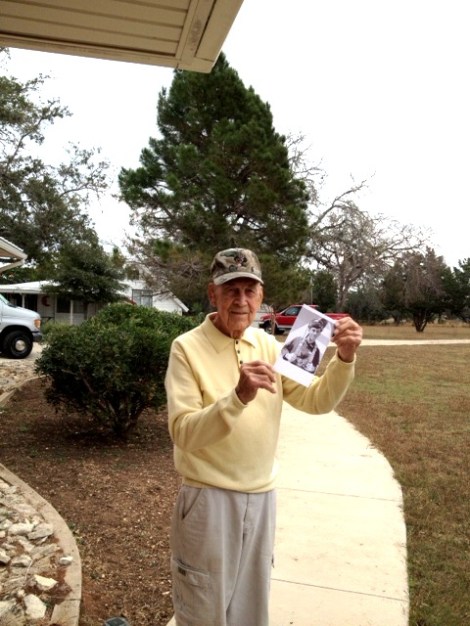

Near the end of the war, Henegar and his crew were assigned a new C-47. The only married one of the bunch, Henegar was given the honor of naming the plane. He chose “Little Oletha.” Henegar proudly showed a black-and-white photo of a strapping young man in a jumpsuit, standing under the plane with his wife’s name painted on the fuselage.

After the war, Henegar flew back to the States, landed in Boston and hopped a bus back home. Oletha drove to pick him up at the bus station in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was swarming with giddy GIs who grabbed any female they could.

“They would run if they saw a woman, and they would hug her and kiss her and fling her in the air. They were so happy the war was over,” she said. “Most of them were drinking. It was wild.”

Oletha wanted none of that, so she hid behind a tree and snuck into the terminal. She was at the door of the bus station when Henegar stepped off the bus. “Oh, he looked wonderful. He was a very handsome Air Force guy,” Oletha recalls. “He still is. I was thrilled to death because he came back whole, and I felt for the ones who came back the other way.”

“We spent lots of time kissing and hugging, and we couldn’t keep our hands off one another,” Oletha said. “We were looking forward to being together again.”

The couple had two children and moved to Texas, where Henegar spent 37 years in the energy business, making use of the skills he developed in the military to operate electronic instruments to find oil for Phillips Petroleum Co. and Chevron. This year, the Henegars marked 73 years of marriage.

“I’m proud that I served in the war,” said Henegar, 95, who lives in Livingston. “You just do what you’re supposed to do. And I thank the Lord for watching over me.”

‘I thought it was angels coming’

In July 1945, L.D. Cox was a 19-year-old helmsman aboard the USS Indianapolis, a heavy cruiser that carried a secret wooden box across the Pacific to the small island of Tinian. He later learned the box contained parts and enriched uranium for the atom bomb nicknamed “Little Boy,” the weapon loaded on the aircraft Enola Gay and dropped on Hiroshima.

Just after midnight on July 30 and one week before the dropping of the atom bomb led to Japan’s surrender, Cox’s ship was struck by two torpedoes fired by a Japanese sub. The more than 600-foot-long Indianapolis sank in just 12 minutes, resulting in one of the most dramatic stories of the war.

With the ship quickly going down, Cox put on a life preserver and handed one to the ship’s captain, Charles McVay. In the ensuing chaos, the captain ordered the sailors to abandon ship.

For the next four days and five nights, Cox and hundreds of men floated, most without food and water. Many men died of dehydration, drowning and attacks by sharks, which Cox could see circling under the surface. Some hallucinated and swam off, never to be seen again. Dying of thirst, one sailor removed his life vest, went under to drink the saltwater and died within about two hours with brown foam around his tongue and mouth.

Cox floated with a pack of about 30 others. A couple of days after the sinking, Cox remembers a shark surfaced and locked onto a sailor floating only three feet away from him. “He came up like lightning and took him down and you couldn’t see anything else,” Cox said.

Cox and the remainder of his group who survived slowly sank lower and lower in their waterlogged life preservers, their noses barely above the water after being afloat more than 100 hours. They were finally rescued when a U.S. pilot saw them by chance one afternoon. Ships were eventually dispatched and picked them up after dark. Cox remembers seeing a spotlight shining up into the dark sky, a beacon of hope from a ship that many sailors later said saved their lives by giving them the will to hang on. “I thought it was angels coming,” said Cox.

The sinking of the Indianapolis resulted in the deaths of almost 900 of the 1,200 men on board. McVay, who also was rescued, was later court-martialed for failing to zigzag to avoid torpedo attacks, a controversial rebuke that Cox and other survivors never have supported.

After the war, Cox graduated from Texas A&M University, served as state sales director for a livestock feed company and operated a ranch. He still owns an 800-acre cattle ranch and lives in Comanche with his wife of 63 years, Sara Lou.

Only the grace of God—and his strong will to survive—allowed him to live, said Cox, 86, who frequently speaks to groups of schoolchildren about his war experience. Unlike some senior citizens chagrined by young generations, Cox expresses optimism and encourages elders to impart strong moral leadership and guidance on today’s kids, who one day will lead the country.

“What I tell them is freedom is not free,” Cox said. “Somebody has to fight to keep our freedom.”

Read more stories of WWII vets.