Shortly after sunrise, Seaman 1st Class Richard Cunningham and two other sailors, Earl Kuhn and Bill Morris, boarded a wooden boat tethered to their battleship, the USS West Virginia. They got underway at 7:50 a.m. and motored across the placid water. Theirs was a most routine assignment that morning: cross the harbor to a dock near the officers’ club where several officers waited for a pick up.

Despite all the talk of an impending war, crews were not on high alert. December 7 was a Sunday and Sundays were leisurely. Sailors were at ease. Officers slept onshore. Some men nursed hangovers from a Saturday night in Honolulu, others gathered for Sunday morning services topside. Watertight hatches and doors on the big warships–compartments designed to confine damage and flooding to a small area in an attack–were open.

The day before, Cunningham took shore leave and shopped for a Christmas gift for his mother. He bought her a cameo brooch, which he stored in his locker beside his bunk on deck.

After a restful night’s sleep, Cunningham was dressed in his Navy whites and stood on the boat’s wooden deck to enjoy the cool breeze. Looking across the smooth water, he held onto the sparkling brass railing, shiny from the endless hours of polishing by Cunningham and the crew.

Suddenly, the calm was shattered by loud sounds and the sight of torpedo bombers swooping down directly overhead and skimming the water’s surface. Cunningham found himself with a front-row seat to one of history’s biggest events—the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Cunningham remembered looking up and recognizing the red discs on the sides of the Japanese torpedo bombers, discs sailors called big red meatballs.

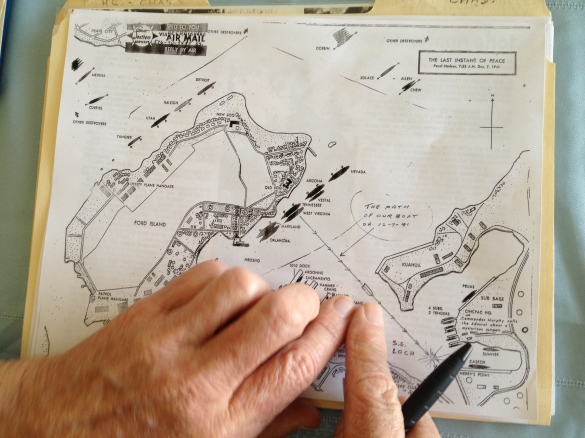

“At 7:55 we’re right here and we’re facing these torpedo planes,” Cunningham said pointing at the spot on a map he had carefully written “the path of our boat on 12-7-41.”

“There was a big blast and we saw those two meatballs and we said to ourselves, ‘This is it! This is it. Those are Japanese and we’re at war. This is no training. This is no drill.’ ”

Seventy-one years after that day, the silver-haired Cunningham told his story while at the home in Hewitt, Texas he shares with Patty, his wife of twenty-nine years. He is among the few people still alive to witness firsthand the event that thrust the United States into World War II.

Cunningham is a retired aerospace industry employee who has spent most of his life in Texas. He grew up in Irondale, Ohio, the eldest of four. His father, a veteran of WWI, worked in a brickyard and the family lived in the back of a grocery store during the dark days of the Depression. Cunningham learned to fish and hunt rabbits and groundhogs.

“I grew up with a gun in my hand,” he said. “I kept my family in meat.” After graduating high school, one of Cunningham’s buddies, nicknamed Little Joe, pestered him to join the Navy.

“He asked me one time too many times.” He told Little Joe, “Let’s go!” Cunningham was attracted by a steady military paycheck. They enlisted in Youngstown. They trained at the Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago and then went separate ways. Cunningham shipped off for duty on the 623-foot-long USS West Virginia, commissioned in 1923 and yet still the nation’s newest battleship. It was being refurbished at the naval shipyard in Bremerton, Washington. Cunningham’s first job was to scrape barnacles off the sides of the ship. In late 1940, it relocated to Pearl Harbor with the rest of the Pacific fleet.

As with other WWII veterans, Cunningham is something of an amateur historian. Close at hand was a stack of a half dozen manila folders filled with war-related documents, photos, and maps, as well as war books, including one entitled Betrayal at Pearl Harbor: How Churchill Lured Roosevelt into World War II.

At age ninety-two, Cunningham retains a good memory. He has memorized more than four hundred gospel and bluegrass songs and plays the mandolin and guitar. The challenge in interviewing him was his hearing difficulties, and he often turned to his wife to relay questions. “Patty is my second ear,” he said.

He carefully laid on his kitchen table an aerial map of what Pearl Harbor looked like that morning, including the location of all the major ships and facilities. The West Virginia and six other battleships were anchored two-by-two at Ford Island, a 330-acre isle in the middle of Pearl Harbor used by the U.S. Navy to moor ships, for an airfield, barracks and other facilities. All around the harbor there was a mighty assortment of ships: another battleship, the USS Pennsylvania, was in dry-dock at the Navy Yard, plus nearly ninety others: destroyers, cruisers, tenders, survey ships.

Cunningham continued his story. “One after another, we’re facing these torpedo planes. You’d look up and see these guys, and they’re grinning from ear to ear. They had the machine gunner behind them. But the pilot of our boat, Earl Kuhn, he kept that boat right underneath these Japanese torpedo planes. The planes were dropping torpedos, which were running under and beside our boat. But he kept it there because had we cut and run I wouldn’t be talking to you now because the machine gunner would have got us. We’re right underneath and the machine gunner can’t shoot down.”

Alarms and general quarters announcements sounded, calling all sailors on ships, as well airmen at Hickman and other airfields, to battle stations. In four minutes, Cunningham witnessed one of the first American shots of the war. Two sailors on the USS Sumner, a survey ship moored at a nearby submarine base, fired its World War I-era guns. They hit one of planes point blank.

“There was a ball of fire so close that it singed my eyebrows and the hair on the back of my hands,” Cunningham said, wide-eyed, remembering the scene. “And the plane just disappeared. The ball of fire just melted it. And the propeller went spinning toward Kuahua [a peninsula that housed a new supply depot].”

The action report filed by the ship’s commanding officer following the attack corroborates Cunningham’s story:

0757 Signal watch and quartermaster on bridge sighted approximately 10 dive bombers, marked with red discs, attacking Navy Yard. …

0759 Went to general quarters. Observed torpedo planes approaching from S.E. over Southeast loch, attacking BB’s [battleships] at Ford Island Mooring Platform, circling Ford Island, and flying off to S.W. Red discs plainly visible on planes.

0801 … Gun crews opened fire immediately on manning guns without waiting to establish communication with control. … Sumner was first ship in vicinity to open fire. …

0803 Torpedo plane passed close aboard, within about 100 yards of Sumner’s stern, on W. course, altitude about 75 feet, leveled off for launching torpedo at BB’s. Plane continued on its course until it was about 300 yards distant from Sumner’s stern, wh[en] it was struck by a direct hit from Sumner’s No. 3 A.A. gun. Plane’s gasoline tank believed ignited, as plane immediately disintegrated in flames and sank in fragments. Torpedo believed sunk without exploding. …

Cunningham saw the eighteen-foot torpedo of the vaporized plane fall into the water. “It went straight down and then it came back up. It resurfaced. When the torpedo came back up it started going in an erratic fashion like this,” he said, holding out an arm and moving it back and forth. The torpedo locked onto their boat. Though the hull was made of wood, it had a metal motor, and it headed right for them. Japanese torpedoes were equipped with honing devices to fix onto metal objects.

“So the coxswain–old Kuhn–put the pedal to the medal. We went into the dock area near the officers’ club landing. Bill Morris was the bow hooker and he had his line in hand and I was the stern hook and I had my line in my hand and we both, we swear, we jumped six or seven feet to that landing. That was the fastest tie-up in history that day [laughs].” The three men ran up the landing and ducked behind a concrete abutment, hoping to avoid the explosion. “We made it and we thought there would be the big explosion when that torpedo hit that dock. But it didn’t happen.” They peeked up over the abutment to see that the torpedo had beached itself on a sandbar between the dock’s pilings.

They looked across the harbor could see the whole thing, the whole attack, as enemy planes continued to pour in, fires raged, and smoked filled the air. “At 8:10 we saw the Arizona blow up. We saw the Oklahoma turning over, and found the West Virginia taking torpedo hits.”

They ran back to their boat and headed right back into the harbor, its water slick with oil and fire. As ships began to fall, hundreds—thousands—of men jumped or fell into the water. Cunningham and his men picked up “boat load after boat load” of them.

“We’d pick these guys up out of the water and we’d bring them to the submarine base. This is still the first attack.” They watched as men wrenched themselves from portholes barely 18 inches in diameter, their eyes wide and their faces frenzied as Cunningham and the others pulled them into their small ship.

“You wouldn’t believe how some of these guys would open the porthole and the water was rushing in and they pulled themselves up against that water, out the porthole, and came up to the surface,” he recounted. One man was so panicked, so frantic, that Cunningham hit him just to get him to settle down.

“He was like a mad man. I hit him with the fist. It might have been the wrong thing to do but [I had] to settle him down, and he did. He sat. He was no problem after that and we picked up some more men and put them in there with him. And then we got over and carried them over to the submarine base and let them out.”

In the first of Japan’s two waves, all the battleships took bomb and or torpedo hits. The USS Oklahoma turned over and sank. The USS Arizona was mortally wounded by an armor-piercing bomb that ignited the ship’s forward ammunition magazine and the resulting explosion and fire killed 1,177 crewmen, the greatest loss of life on any ship that day. The California, Maryland, Tennessee, Nevada, and Pennsylvania also suffered heavy damage.

Cunningham’s ship, the USS West Virginia, was hit by two armored-piercing bombs through her deck and five aircraft torpedoes in her port side. Heavily damaged by the ensuing explosions, and suffering from severe flooding below decks, the crew abandoned ship while the West Virginia slowly settled to the harbor’s shallow forty-five-foot bottom. Of the 1,541 men on the West Virginia, one hundred and thirty were killed and fifty-two wounded.

The second attack came about an hour later.

“The second attack was bombs mostly. We stayed out in the harbor. The thing is when these guys released these bombs they would take a pass at us with their machines guns. One of them knocked out a window in our boat. None of us three got hit. But of course the boat, had a couple bullets in it [(laughs].”

“We stayed out in the harbor getting these guys who were injured to the submarine base. It’s a funny thing but you think about your buddies. You think about other guys and think how you can help somebody else. You don’t go someplace and hide. You get out there and you start looking for some guys you can help and that’s what we did.”

On December 16, Cunningham’s mother received a telegram from the Navy. Her son was lost and presumed dead. The telegram read:

The department extends to you its sincerest sympathy in your great loss. To prevent possible aid to our enemies please do not divulge the name of his ship or station. If remains are recovered they will be interred temporarily in the locality where death occurred and you will be notified accordingly. Rear Admiral C.W. Nimitz, chief of the Bureau of Navigation

It wasn’t until December 19 that the Navy sent another telegram with the news that he was a survivor. Cunningham said he wasn’t able to call to clear the mix up because phones were inoperable.

And, besides, he and his mates were busy with countless duties after the attack, helped put out fires and salvaged ammunition that divers brought up from sunken ships. Orphans as such, with their ship home unavailable, they slept on their boat and lived on peanut butter and crackers they had on board.

After helping put out the fire on the Arizona, the three men headed for what had been their home, the West Virginia.

Pearl Harbor has a mean depth of forty-five feet and battleships have a forty-foot draft. Despite being hit with seven torpedoes on its port side, the West Virginia gracefully sank to the bottom after two sailors opened valves to let water out on starboard side to counter the floodwaters pouring in the port side. This allowed the great ship, longer than two football fields, to settle in a somewhat level position.

Cunningham and his crew tied up alongside. They climbed aboard and waded knee-deep in the black, oily water across its deck. Cunningham found his locker. His belongings were all burned up, including his photo album and even the medals he won for besting other sailors in rowing and sailing competitions. Just one thing was not destroyed: the brooch. Just before Christmas, after being assigned a bunk in a barracks onshore, he mailed it to his mother.

Cunningham served the rest of the war helping to run supply and troop ships that sailed into battles across the Pacific, including Guadalcanal, the Treasury Islands, New Georgia, Rendova, and Bougainville. In one fight, he fired a machine gun at diving Japanese planes, his bare feet on the ship’s railings to avoid hot shell casings that littered the deck. Another night, near New Georgia, his ship struck a reef and all but sank. Some coral kept its bow out of the water and he and his shipmates huddled there and clung for life. They were rescued by a U.S. minesweeper the next day.

In March 1945, remarkably more than four years after he joined the Navy, Cunningham returned home for the first time since he shipped out, an occasion marked by a story in the local paper.

After the war, he had a brief marriage and a long one and four daughters. He moved to Texas and worked in the aerospace industry. Among other things, he wrote and prepared engineering and performance documents on F-111 fighter jets for General Dynamics in Fort Worth. Nearly thirty years ago, he married a third time, to Patty, who also remembers WWII from the perspective of a schoolchild.

In 1993, two years after his mother’s death, Cunningham donated the brooch to the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg where it is on display.

He spoke at my Son’s High School this week for Veteran’s Day!

LikeLike

My father was Earl Kuhn, mentioned in the article. I owned a house in Johnson City, TX for three years and never knew the connection. Is there a chance Mr. Cunningham is still living and I could contact him?

LikeLike

RIchard Cunningham is my grandfather. He is still alive and well here in Waco Texas!

LikeLike